The first poll was annulled. A second may be violently disrupted

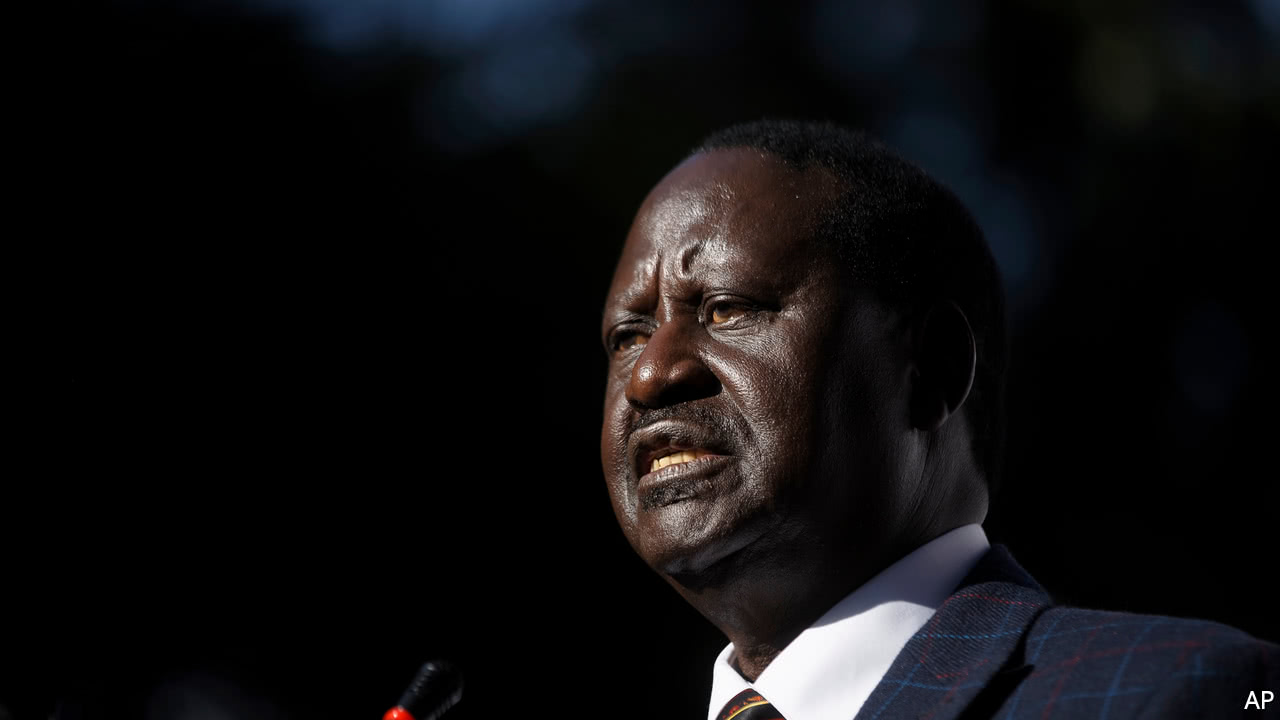

IN THE rickety wooden markets in Nairobi, where traders sell old books, second-hand clothes and kitchenware, walking away is a buyer’s last negotiating ploy. If he is lucky, he will be chased down the street and offered a better price. Raila Odinga, Kenya’s softly-spoken opposition leader, seems to be hoping a similar strategy may rescue his electoral chances.

On October 10th Mr Odinga withdrew from a re-run of the presidential election scheduled for October 26th, arguing that if it went ahead then it would not be free or fair. Courts had already annulled the presidential part of a wider set of elections held on August 8th, after finding problems with the way it was run. But no reforms have been made to the electoral process since then, he argued.

It had already been clear for several weeks that Mr Odinga did not plan to contest the election. His coalition of parties, the National Super Alliance (NASA), had been running a bare-bones campaign. The candidate himself had made plans to travel to Britain and possibly America two weeks before the vote—prime campaigning time—presumably to drum up international support for his withdrawal.

Yet the announcement still contained a surprise. This is because instead of proposing a straightforward boycott, Mr Odinga seems to be hoping that by standing down he will force the courts to halt the election altogether and order a new one in the future after the parties have nominated new candidates.

Under the original Supreme Court ruling that annulled August’s election, the electoral commission has until November 1st to organise a new one. If that deadline is missed, then Kenya will be plunged into a constitutional crisis. It is unclear how that would be resolved. Those in the camp of the incumbent president, Uhuru Kenyatta, want an election to be held no matter what. Some hardliners want him simply to be declared president. In parliament MPs pushed through an amendment to the electoral law that automatically awards victory to the remaining candidate if one of them withdraws from a re-run of a presidential election.

Yet the real crisis is one of legitimacy, not law. Should the courts and electoral commission go ahead with a vote that is not contested by Mr Odinga, his supporters will surely try their best to disrupt it, says Michael Chege of the University of Nairobi. In their strongholds, principally in western Kenya and certain Nairobi slums, they could prevent the electoral commission from holding a vote that would satisfy the courts.

By walking away, Mr Odinga seems to be gambling on his ability to threaten chaos to push Mr Kenyatta to negotiate. But the trouble with that strategy is that Mr Odinga is running out of money. And although opposition protests occasionally gum up the centre of Nairobi, even his most fervent supporters will not stay on the streets indefinitely.

The worst outcome for Mr Odinga is that his bluff is called and the election goes ahead without him. Electoral officials said they plan to do just that. Mr Kenyatta might remain president, but a large proportion of the population would not recognise his right to rule and would feel left out of the political system.

On October 10th Mr Odinga withdrew from a re-run of the presidential election scheduled for October 26th, arguing that if it went ahead then it would not be free or fair. Courts had already annulled the presidential part of a wider set of elections held on August 8th, after finding problems with the way it was run. But no reforms have been made to the electoral process since then, he argued.

Latest updates

Yet the announcement still contained a surprise. This is because instead of proposing a straightforward boycott, Mr Odinga seems to be hoping that by standing down he will force the courts to halt the election altogether and order a new one in the future after the parties have nominated new candidates.

Under the original Supreme Court ruling that annulled August’s election, the electoral commission has until November 1st to organise a new one. If that deadline is missed, then Kenya will be plunged into a constitutional crisis. It is unclear how that would be resolved. Those in the camp of the incumbent president, Uhuru Kenyatta, want an election to be held no matter what. Some hardliners want him simply to be declared president. In parliament MPs pushed through an amendment to the electoral law that automatically awards victory to the remaining candidate if one of them withdraws from a re-run of a presidential election.

Yet the real crisis is one of legitimacy, not law. Should the courts and electoral commission go ahead with a vote that is not contested by Mr Odinga, his supporters will surely try their best to disrupt it, says Michael Chege of the University of Nairobi. In their strongholds, principally in western Kenya and certain Nairobi slums, they could prevent the electoral commission from holding a vote that would satisfy the courts.

By walking away, Mr Odinga seems to be gambling on his ability to threaten chaos to push Mr Kenyatta to negotiate. But the trouble with that strategy is that Mr Odinga is running out of money. And although opposition protests occasionally gum up the centre of Nairobi, even his most fervent supporters will not stay on the streets indefinitely.

The worst outcome for Mr Odinga is that his bluff is called and the election goes ahead without him. Electoral officials said they plan to do just that. Mr Kenyatta might remain president, but a large proportion of the population would not recognise his right to rule and would feel left out of the political system.

No comments:

Post a Comment