For posturing dictators, only putting a new city on the map will do. Fifty years on from Mobutu Sese Seko’s ascent to the presidency of Congo, David Smith explores what’s left of his personal Xanadu, Gbadolite

One hundred thousand trees, 20,000 tons of marble are the ingredients of Xanadu’s mountain. Contents of Xanadu’s palace: paintings, pictures, statues, the very stones of many another palace — a collection of everything so big it can never be catalogued or appraised; enough for 10 museums; the loot of the world ... Since the pyramids, Xanadu is the costliest monument a man has built to himself.”

So trumpets a voiceover in the opening scenes of Orson Welles’s Citizen Kane, the story of a plutocratic newspaper baron and empire-builder: “America’s Kubla Khan”. But we have already seen that Kane is dead and his Florida folly slowly turning into a dilapidated ruin. The same fate has befallen the grandiloquent mansions of other men before and since. But never, perhaps, quite so violently and definitively as that of another journalist turned billionaire with passions for art and politics: Mobutu Sese Seko.

President Mobutu’s personal Xanadu was his birthplace, deep in the jungle of what is today the Democratic Republic of the Congo, the biggest country in sub-Saharan Africa and one of the world’s poorest and longest-suffering. In the early 1970s, Gbadolite was a remote village of 1,500 people living in mudbrick huts and not even marked on maps. But thanks to unlimited hubris and riches, a new town was hacked out of the tropical rainforest, with houses, schools, hospitals, municipal buildings, a five-star hotel, a 3,200m runway for the supersonic Concorde and – the pièce de résistance – three palaces of kleptocratic kitsch.

Gbadolite remains the vision of a totalitarian master builder, like Astana in Kazakhstan, Naypyidaw in Myanmar, Oyala in Equatorial Guinea and one that never got off the drawing board: Adolf Hitler’s Germania. For posturing dictators it seems the transience of power and wealth is not enough. Only putting a new city on the map, shaped in their own image, will do. Each seems determined to take the inscription on Christopher Wren’s tomb at St Paul’s Cathedral to a new level: “Si monumentum requiris, circumspice.” (If you are seeking his monument, look around you.)

This year’s 50th anniversary of Mobutu’s ascent to the presidency of Congo will be no cause for celebration. Congo had just emerged from the catastrophe of Belgian rule: King Leopold II, arguably the most egregious of all colonialists, turned it into a personal fiefdom, killing and enslaving the population to enrich himself with ivory and rubber. But when the CIA helped Belgium assassinate independence prime minister Patrice Lumumba, opportunity knocked for Joseph Desire Mobutu, who had worked as a reporter and editor before returning to the army and climbing the ranks.

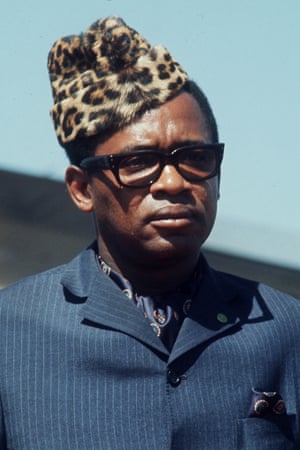

In 1963 he was invited by president John F Kennedy to the White House and effectively recruited to the capitalist side in the cold war’s African battleground. Two years later he declared himself head of state, renamed his country Zaire, renamed himself Mobutu Sese Seko Koko Ngbendu wa za Banga (meaning “the all-powerful warrior who, because of endurance and an inflexible will to win, will go from conquest to conquest leaving fire in his wake”) and adopted his infamous leopard-skin hat.

America, his patron, appeared willing to bankroll or turn a blind eye to any excess. Mobutu rapidly set the tone for his rule by ordering the public hanging of four former ministers at a sports stadium for an alleged coup plot. He continued with a Machiavellian combination of murder, detention and torture on the one hand and bribery, corruption and patronage on the other. The mineral-rich nation’s coffers were looted on a mind-bending scale as Mobutu amassed an estimated fortune of $5bn and lavish properties around the world. “When he left power he was universally excoriated as Africa’s greatest kleptocrat,” noted Mobutu’s obituary in the Guardian in 1997.

There was no greater symbol of excess than Gbadolite and its palaces, for which he hired the Tunisian-born French architect Olivier Clement Cacoub and Senegal’s Pierre Goudiaby Atépa. His private palace, seven miles outside town in Kawele, brimmed with paintings, sculptures, stained glass, ersatz Louis XIV furniture, marble from Carrara in Italy and two swimming pools surrounded by loudspeakers playing his beloved Gregorian chants or classical music. It hosted countless gaudy nights with Taittinger champagne, salmon and other food served on moving conveyer belts by Congolese and European chefs.

Visiting in 1988, a New York Times journalist recorded: “At a marble-tiled terrace, voices rose from banquet tables set against a backdrop of illuminated fountains. Liveried waiters served roast quail on Limoges china and poured Loire Valley wines, properly chilled against the equatorial heat. ‘Bon appetit,’ said the 58-year-old president.”

Guests over the years reputedly included Pope John Paul II, the king of Belgium, French president Valéry Giscard d’Estaing, UN secretary-general Boutros Boutros Ghali, self-declared emperor Jean-Bédel Bokassa of the Central African Republic, American televangelist Pat Robertson, oil scion David Rockefeller, businessman Maurice Tempelsman and William Casey, director of the CIA.

“It was an African Versailles,” says politician Albert Moleka, who reckons $400m was spent and recalls how in 1985 France’s Gaston Lenôtre, the leading pastry chef in the world, flew in on Concorde with a birthday cake for Mobutu. “It was a big decorated cake with white cream. Another time he invited Paul Bocuse and other top chefs from Europe for a special occasion. Normally Mobutu liked traditional local food, like antelope, and fish and eels. He also had one of the best wine cellars in the world.”

Mobutu once presented Moleka, now a senior member of the opposition Union for Democracy and Social Progress, with a bottle of Cheval Blanc of 1928 vintage. He lost it when the president was toppled by rebel Laurent Kabila and Moleka’s home was ransacked.

The end of the cold war had left Mobutu living on borrowed time and, suffering from prostate cancer, he fled the country when Kabila’s troops marched a thousand miles to Kinshasa, the capital, in 1997. He died in Morocco shortly after, aged 66. The home of the looter-in-chief was now itself stripped bare by soldiers who smashed furniture, tore down silk wallpaper and stole everything down to the last bauble in an orgy of pillaging.

Just 18 years later, this Xanadu is a pathetic and pitiful shell, a mockery of Mobutu’s insane opulence. A decaying brown and gold gateway still stands on the edge of the grand estate opposite a cluster of small homes made from mud, wood and dried grass. Mami Yonou, 26, who lives among them, comments: “We are not happy how much Mobutu spent while local people were suffering, although he brought us gifts and clothes and money.”

Children heave rusting pieces of scrap metal to allow vehicles access, past vegetation and anthills and the control box where security staff would once have vetted visitors, up a winding drive of nearly 3km – doubtless once intended to intimidate or awe those in each Mercedes back seat. Finally, through a tunnel clad with rough red bricks, there it is: a tiered fountain in the style of Versailles that used to play instrumental music. Now the giant circular bay that once held water is dry, cracked and sprouting weeds.

Beyond it is the imposing entrance arch and, up four steps, what was once the atrium with a dozen marble-clad pillars and what was presumably another fountain with statues of lions on each corner. Only two of the forlorn big cats are still in position. Slightly off centre is a long corridor that leads to Mobutu’s old bedroom. Here the showman could proudly flick a switch and, through a hidden mechanism, panels would slide apart to reveal his bed, rising from the floor as if by magic, flanked by bronze sculptures of females named “The Sleep” and “The Wake”. Now that same alcove contains a pond of green slime.

The entire roof of the palace has gone, leaving only a skeleton of red steel girders punctuated by tall trees. Mattress foam, smashed marble and slivers of glass crunch underfoot. Slowly but surely, the palace is being reclaimed by the jungle. Bushes, flowers, vines, weeds, even trees shoot up through every available crevice in a living testimony to the fragility of civilisation. Hives and nests cling to the walls. From a winding marble staircase springs a single pink flower. In what is said to have been the bedroom of one of Mobutu’s sons, who was nicknamed “Saddam”, a spiky tree trunk rises higher than what used to be the ceiling.

At the back of the palace is a veranda where, in a screenwipe of imagination, one can picture dapper-suited diplomats sitting on sultry evenings, making smalltalk over a gin and tonic and watching the setting sun amid a chorus of crickets. One thing remains unchanged – the vista is stupendous: the green, tree-dotted, hilly landscape of an Africa seen in so many nature documentaries and tourist fantasies.

The old kitchens lie empty save for graffiti and ominously hanging insects. In other rooms are the twisted remnants of chandeliers, four cables dangling at crazy angles, and two shards of an Asian vase portraying a red fish. The surrounding terrain includes a toilet bowl discarded in thick grass and the rusting skeleton of a burned-out car succumbing to the embrace of a tree.

Down an overgrown staircase at one side are two swimming pools, their crumbling blue tiles again yielding to multiple flora and long grass, with algae dominating the little vestige of water. Bees buzz and make honey above the bigger one. The former garage has been gutted and coated with sharp-edged rubbish, but above, sections of a faux-classical ornamental wall are still intact.

Yet the shattered palace is not quite deserted. It is still haunted by a handful of Mobutu loyalists whose parents or grandparents used to work here. They charge visitors $20 for a tour, carry out routine maintenance to prevent it turning to dust, and hope that one day the old autocrat’s children, who continue to dabble in politics, will restore it for the nation. Among them is Francois Kosia Ngama, 30, whose grandmother was a teacher to Mobutu’s mother. In its heyday, he recalls, the palace employed 700 to 800 chauffeurs, chefs, servants and other staff, plus more than 300 soldiers. There are many more rooms underground that can now longer be accessed, he says. “When I used to come here, I would feel I was in paradise. It was wonderful. Everyone would eat according to his wish.”

Remembering the days when Concorde came to town, he beams and stretches his arms wide. “It was this big. Its nose pointed up. Before it arrived, Mobutu informed everyone and sent lorries to take them to the airport.

“People were poor but at the time we couldn’t see it. We thought everyone was OK. The army was organised and well paid. There were clothes from the Netherlands and women had money to buy them. In education, teachers were on good salaries and couldn’t complain too much. Some needed big bags to carry all the money each time they were paid. Most teachers had their own means of transport but now it is not the case. Coca-Cola employed 7,000 people but now they are unemployed.”

The decline of Mobutu’s palace fills the jobless Ngama, who has been caring for it for 10 years, with sadness. “A white man from France came here and when he saw it, he wept. I take care of this place because it’s from one of our own. Although Mobutu died, he left it for us.”

This palace and two others in Gbadolite – one designed as a cluster of Chinese pagodas, the other for state business and now occupied by the military – are in terminal decline, but the town itself survives with a population of 159,000, a bustling marketplace and a sprinkling of bars and restaurants. It has more night-time brightness than many remote parts of Africa thanks to a hydro-electric dam that Mobutu built on the Ubangui river in 1989.

Without presidential patronage, however, Gbadolite too has seen better days. The Coca-Cola bottling plant shut down and was turned into a UN logistics base. Concrete multi-storey municipal buildings were halted mid-construction and became improvised schools, breaking every health-and-safety rule in the book as they throng with children in blue and white uniforms. The once pristine Boulevard Mobutu has lost its lustre.

The compound that oversaw industry during the boom years now has a fading, almost unreadable sign and a deathly hush. Jean-Nestor Abia, 50, who has worked here since 1984, says: “We are weeping because Mobutu is no longer alive. He was like my father. I loved and worshipped him. He was not a dictator – he was a good man who wanted to unify people.

“At the palace I was at ease, I was happy. He would hold my hand and say, ‘You are a good friend of mine.’ I thought, how could I be with the president of the republic? It was exciting. He would joke with me: when I was eating, he would take my spoon and eat with it. At that time we thought Mobutu would never die. We thought he was eternal.”

The five-star Motel Nzekele, opened in 1979 with decor to match, still has an image of Mobutu at the front gate but can only offer ghosts in its shabby reception, arid fountains and pools, red-walled bar and nightclub with exotic paintings of bare-breasted women. The empty cinema has ripped seats and holes where the projector used to be. To stay in one of the hundred rooms costs $50 a night.

The pope, the Belgian king and French president François Mitterrand all stayed here, says coordinator Gustave Nbangu, 49, explaining: “It was a beautiful hotel, five stars. It was a great centre of development. Remember this was once a jungle, a forest, with nothing here. But Mobutu was born here and when he became president he decided to build this and settle his people. He was like the father of the family.”

No one could accuse Mobutu, who brought Muhammad Ali and the eyes of the world to Kinshasa for “the rumble in the jungle”, of failing to think big. Gbadolite airport enabled him to charter Concorde, the fastest passenger plane in the world, for extravagant trips to Europe. In 2015 the vast runway, bordered by wild growing grass, welcomes only two or three tiny aircraft a week from the UN and one commercial operator. Most of the portable staircases lie idle and broken near the remnant of a helicopter engine and a row of flagless poles while, at the top of the defunct control tower, two windows lie shattered on the floor.

At the check-in desk a luggage conveyor belt appears long dead, while wall paintings of topless women and muscle-bound men are peeling away. Up a stairway that lacks bannister or handrail, 25-year-old mosaics of African villages are surrounded by graffiti. At the nearby VIP arrivals lounge, uniformed soldiers camp out with music pounding from a stereo. The airport office has no record of Concorde’s flights here. The paperwork was lost for ever when the town fell and, like so much else in Gbadolite, that moment in the sun is fading into mythology.

But Mobutu survives in another image outside the mayor’s office. The painting depicts him in crisp white military tunic with cap, spectacles and green sash, his hands gripping a rail as if surveying an adoring public. Egide Nyikpingo, who has been mayor for seven years, says industry died out with Mobutu. “When I arrived in 2008 I was sad at the way the airport looked. When I drove from the airport to downtown, I felt very sick. We destroyed our most beautiful town. I still feel sad about it.”

Nyikpingo, 42, is aware of the ambiguities around Mobutu’s legacy. “He was a dictator. Everybody knows that. But the local people don’t mind the way he was behaving. They still like him. He did well when he decided to build this town, but the social conditions were not equal for everyone.”

Seven hundred miles to the south, in Kinshasa, there are still some who remember Xanadu’s landlord fondly. Alfred Liyolo, 71, one of Congo’s leading sculptors, sold several bronzes to the palace in Gbadolite and designed a church and tomb for Mobutu’s first wife; all were lost or destroyed in the looting. “He was a dictator, that’s right, but he was also a builder,” Liyolo insists. “He was a man of culture who wanted his home furnished by local artists. He was generous and allowed local artists to be known throughout the world and immortalised.

“But after his death, people destroy and don’t preserve. Today the town is just a shadow and nature has taken back its right. If I went back there today, I would feel desolation.”

Elias Mulungula, who was Mobutu’s interpreter for four years, echoes the sentiment: “If I go to Gbadolite today, I can’t avoid crying just as Jesus cried when he beheld Jerusalem.”

Mulungula, 52, went on to become a government minister but admits: “I always feel more proud when people greet me as ‘Mr Interpreter’ than when they say ‘former minister’. Being interpreter for Mobutu was a privilege. He was a very kind leader, a gentleman. He couldn’t eat without making sure other people had eaten already. He was open and liked making jokes.”

Unswervingly devoted, Mulungula adds: “President Mobutu was a positive dictator, not a negative one. He knew what methods to use to preserve unity, security and peace for his people. You could feel at home anywhere in the Congo under Mobutu’s regime. There is no freedom without security. He understood what the people needed at the time.”

Even Mobutu’s long-time foes suggest that he was preferable to the current president, Kabila’s son Joseph, whom they accuse of corruption, human rights abuses and attempting to cling to power beyond his term limit. Joseph Olenghankoy, arrested 45 times by Mobutu’s regime and subjected to electric shocks in prison, argues: “With Mobutu we had a state, but he was a dictator. Today we don’t have a state – it’s a jungle. Kabila is killing more than Mobutu. Kabila is three times richer than Mobutu. Mobutu was respected in the international community; Kabila is doing things in a wild and brutal manner.”

Olenghankoy, president of the opposition Forces for Union and Solidarity party, also expresses sorrow at the decline of Gbadolite. “Mobutu is a man, he is gone, but all these things should remain state property. The mistake of this country is they have destroyed and looted everything. They were doing that to rub out Mobutu’s memory, but the history should be preserved. The history might be positive or negative but it remains our history and we should pass it from one generation to another.”

The palace at Gbadolite is testament to the death of memory. In the final scenes of Citizen Kane, the protagonist’s childhood sledge, “Rosebud”, is thrown on a fire and lost. For Mobutu, the final surrender is to flowers, leaves and the African wilderness.

No comments:

Post a Comment