It is impossible to imagine the sequence of events that led to the utter terror and appalling fate of 700 souls lost off the Mediterranean coast last weekend – only days after 400 others drowned in a similar incident en route to Europe. Meanwhile, new tragedies unfold off Rhodes, with further loss of life at sea, and the Italian and Maltese navies respond to other vessels filled with hundreds of Africans. Images of boats unable to contain any more humanity challenge and almost defy our compassion.

How do you encompass such a situation? Individual stories only leave us lost, unable to comprehend the choices that have led to this. Mohamed Abdallah, a 21-year-old man from Darfur who had left war-torn Sudan for Libya only to find another war there, said: “There is a war in my country, there’s no security, no equality, no freedom. But if I stay here, it’s just like my country … I need to go to Europe.”

The numbers involved in this ongoing tragedy are staggering. Last year, 220,000 migrants without papers came to Europe by sea, according to the European border agency Frontex. Of those, about 67,000 were Syrians fleeing civil war. Others were escaping brutal dictatorship in Eritrea, or the civil war in Mali. Many were simply motivated by poverty in sub-Saharan Africa.

Some pay smugglers $10,000 – 18 times the average salary – for their “ticket” to freedom. Others have to pay in instalments as they progress towards Libya or Niger. Italian officials estimated that, in 2014, 600,000 migrants were waiting in Libya to come to Europe. The ships they board are often unseaworthy. Once the migrants realise this, many resist boarding, and are forced on by smugglers wielding knives. As they approach European waters, the smugglers make their passengers leave the ship and board inflatable rafts, abandoning the migrants to their fate. When one group refused to leave the ship last autumn, the smugglers rammed the vessel and sank it, drowning up to 500 people.

There are historical parallels here that only underline the desperation of the situation. While in Rome Pope Francis has called for the sea not to be turned into a cemetery, Italy has ceased its rescue programme, Mare Nostrum, which critics said only encouraged migrants. The name is a telling one, since it was ancient Rome that declared the Mediterranean Mare Nostrum, “our sea” – an evocation of imperial power, rather than responsibility. That phrase was replaced by Mare Liberum, a free sea, a phrase that speaks to the notion that the ocean can liberate. That is why contemporary migrants place their trust in it.

Migrants suffer dreadfully in such voyages. In one incident, reported by Médecins Sans Frontières, a woman with a six-month-old baby who was crying was told by a smuggler to shut it up. “I have nothing to give to him, not even water,” she said. “Where can I get some water?” The smuggler threw the infant into the sea, telling her: “Now he can drink water.” Nor are these scenes confined to Europe. One woman fleeing Iraq for Australia was interviewed after the ramshackle vessel she was on sank. “The boat broke up within seconds; the waves washed the family members apart. I saw a woman giving birth in the ocean, I saw my brother being washed away by the waves, I called out to him but saw him weeping.” This week, one Lampedusa fisherman told Newsnight: “We often pull up skulls and bones in our nets.”

There is an almost biblical scale to this transcontinental tragedy, one that shames our western sense of security. At the same time, it evokes the elemental struggle presented by the sea; the hope that it presents, and the terrible consequences of placing any trust in it. The sea does not care. After the sinking of another immigrant ship off Lampedusa in 2014, it transpired that the economic refugees had been led to believe that they would sail from Africa straight into London itself, as if on to golden pavements. It is a scenario that invokes Joseph Conrad’s doomy opening to Heart of Darkness, in which he imagines the Thames estuary opening out to the world in its imperial reach – “an interminable waterway … leading to the uttermost ends of the earth” – one that will end in the African river by which Colonel Kurtz has established his tyrannical sway.

Conrad was drawing on the terrible events in the Belgian Congo under Leopold II, themselves the consequence of two centuries of exploitation of the continent – most especially in the slave trade. Indeed, this last contemporary tragedy at seaevokes other terrible images of maritime disaster.

In his extraordinary painting The Raft of the Medusa, the French artist Théodore Géricault portrayed the infamous aftermath of the sinking of a French naval frigate that had set sail in 1816 to colonise Senegal under the command of an inept captain. When the ship ran aground off Mauritania, 150 survivors clung to a raft. After 13 days of brutality and cannibalism, only 10 would remain alive. Géricault’s work depicts their vain hope – a rescue boat is glimpsed on the horizon, sailing away without having seen them. When the huge canvas was exhibited in Paris in 1819, it created a sensation. Many were repelled by its scenes of corpses; others, such as the historian Jules Michelet, declared: “Our whole society is aboard the raft of the Medusa …”

They are words that echo today. At the head of the raft, a black man waves a red shirt. The artist’s inclusion of a person of colour has been seen as a reflection of his support for the abolition of slavery. Critics have noted that the painting’s exhibition in London was deliberately planned to stoke anti-slavery agitation in Britain.

Reduced to helplessness, we might turn to art to make some sense of such scenes. JMW Turner’s painting of 1840, Slavers Throwing Overboard the Dead and Dying – Typhoon Coming On, itself influenced by Géricault’s work, drew on Turner’s reading of Thomas Clarkson’s The History and Abolition of the Slave Trade. In it, Clarkson described how, in 1781, the captain of the slave ship Zong had thrown 133 slaves overboard in order that he could collect insurance payments. And like Géricault’s work, Turner’s composition was used to political ends. His painting was displayed to coincide with a meeting of the British Anti-Slavery Society, and Turner had lines from his own poem set next to it: “The dead and dying – ne’er heed their chains / Hope, Hope, fallacious Hope! / Where is thy market now?” (This purgatorial “Middle Passage”, during which so many African men and women died, has also become the subject of contemporary art too. In her work Watery Ecstatic, the black American artist Ellen Gallagher, whose parentage is part Cape Verdan, part Irish, explores the notion of Drexciya, an underwater utopia peopled with the babies of pregnant African slave women thrown overboard in the mid-Atlantic.)

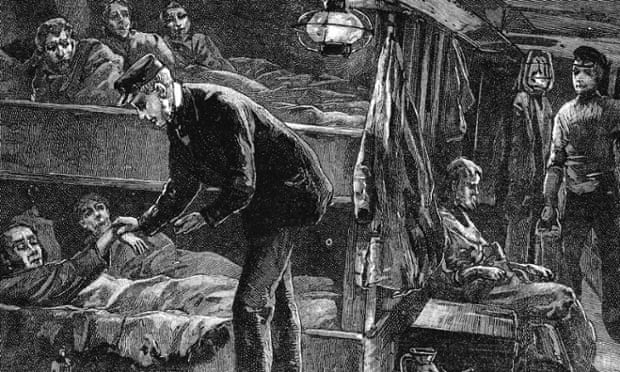

Despite moving towards abolition in the 1820s, the British empire turned to another forced migration by ship: that of transportation, during which thousands of men and women (including my own ancestor) were sent to New South Wales and Van Diemen’s Land (now Tasmania) in appalling conditions. Many died during the voyage, chained and crammed in holds in conditions no better than those of the African slaves bound for the Caribbean. They spent up to three months in the dark, with disease running rife. So bad were conditions that one ship’s surgeon, serving on the convict ship John I, sailing from Portstmouth to Van Diemen’s Land in 1830, threw himself overboard “in a fit of lunacy”. Three years later, in 1833, another convict ship, the Java, left Cork bound for New South Wales, laden with 200 transportees – among them 12 insurrectionary Whiteboys from Kilkenny, found guilty of swearing an illegal Whitefoot oath. Their horrific passage was recorded by the ship’s surgeon, who noted, in the Java’s journal, that the Irish prisoners suffered far more on the passage because they were so undernourished.

Only a decade later, and a new migration had swelled on the edges of Europe. In the mid-1840s, thousands of economic migrants left Ireland (a country then the most impoverished in Europe) when the potato crop failed and created what became known as the Great Hunger, or Famine – despite the fact that throughout the crisis Ireland was also exporting grain to Britain as its population starved. Evicted from their often rudimentary huts, known as scalps, those who survived starvation also faced terrible voyages across the Atlantic in “coffin ships”, so-called because so many of their human cargo died of disease or malnutrition en route, or shortly after arrival. One infamous coffin ship, the Pomano, said to be rotten and carrying entire families evicted from County Sligo, sank on its way to America. All on board were drowned.

Barely a century and a half ago, the British Isles were witness to scenes as desperate as those now being enacted in the Mediterranean. In 10 years from 1845 to 1855, more than two million Irish migrants left for North America. In 1847 alone – “Black 47” – 50,000 perished en route to the new world, or shortly after they reached it. Ships that had brought timber, tobacco or cotton to Britain and Europe were restocked and overpacked by greedy masters to maximise their profits on the return journey. Their dying cargo – human ballast – was dumped overboard like a grotesque watery paper trail. Some sidestepped the process and threw themselves over and into “the seething waters”.

In New York, those Irish immigrants who had survived the crossing found themselves in the same state of penury. Many squatted in the wastelands of Brooklyn in the 1850s and 1860s, “lying in the very heart of the city, and given over to hogs and cows, and to the squatter sovereigns who have erected wretched shanties upon it”.

Slaves and transportees had no choice but to leave. The hungry and dispossessed have a choice, but it is hardly much of one. As a consequence of the Irish Famine, thousands left from Cobh’s quaysides, their worldly possessions parcelled up in brown paper, wearing their best clothes. Herman Melville wrote of such scenes in his autobiographical novel Redburn, an account of his first sea voyage from New York to England and back. On his return journey, hundreds of migrants boarded his ship at Liverpool. The other cabin passengers were protected by their 20 guinea tickets “from the barbarian incursions of the ‘wild Irish’ emigrants”, who were kept in parlous conditions below deck, “stowed away like bales of cotton, and packed like slaves in a slave-ship”. Melville describes their journey as fraught with sea-sickness and poor provisions, “cut off from the most indispensable conveniences of a civilized dwelling”. Deceived by ship owners about the shortness of their passage, they were allowed on deck to see the sea, only to mistake the coast of their own island for America as they sailed across the Irish Sea.

I write this from the shores of Cape Cod, where a storm has risen up and is dashing spit-green waves against the bulkhead of this beach house. This part of the Cape is known as the Shipwreck Coast. Only a century ago, an average of two ships a month were wrecked on this Atlantic strand, in seas so high that those on the shore could only stand and watch as the passengers and crew of vessels perished in the tumult. Some who did survive might be cast up on shore at night, only to freeze to death.

Four hundred years ago, this bay was witness to the migrants fleeing persecution: the Pilgrim Fathers who had left England for the new world. They too paid a crew to bring them here, suffering storms and near starvation to reach what would become New England. Even as they left Southampton, and before calling at Plymouth, they were subject to the “cunning and deceit” of their ship’s master. And here in Provincetown, where they finally made landfall, four of their number died, on what were then desolate, sandy shores. In our secure western world, we look out to a sea we have conquered and called into our dominion, exploited and even polluted in the process. But that same sea offers thousands a different hope. For them, it is a last resort.

Philip Hoare’s latest book, The Sea Inside, is published by Fourth Estate at £9.99. To order a copy for £7.99, including free UK p&p, go to bookshop.theguardian.com or call 0330 333 6846.

No comments:

Post a Comment